The Importance of Recirculation in Microfluidic Systems: Principles and Applications

Microfluidic Recirculation in Life-Sciences: Principle, advantages, key tips for your set up. How to choose the right flow controller for recirculation and more..

Overview of Microfluidic Recirculation

Microfluidic recirculation refers to a configuration in which fluid (e.g., cell culture medium or reagent) is circulated in a closed loop through a microfluidic chip or chamber constantly in the same direction. Single-pass flow configurations such as injection and perfusion are when the fluid from the reservoir through the chip, is discarded to waste.

Each of these set ups has their applications. Recirculation allows the same volume to pass repeatedly, which is advantageous when medium or reagents are expensive or limited. Simple microfluidic perfusion is advantageous for applications like pancreas ex-vivo perfusion or single cell assays.

Read further to find out different recirculation set-ups possible with pressure-based technologies, main advantages and applications in cell biology.

Main Advantages of Microfluidic Recirculation

When designing a recirculation setup, especially for life-science applications, these parameters are critical:

- Flow stability vs. Pulsatility: steady laminar flow matters for sensitive cells

- Unidirectional flow with recirculation: to simulate physiological perfusion, i.e. veins and arteries. This often requires active or passive valves to prevent backflow.

- Medium volume vs cell volume ratio: recirculation reduces the volume of medium needed. This can be important when medium is expensive or primary cells are limited. It also allows to amplify the secreted metabolites.

- Shear stress: precision in flow control translates to shear stress control within microfluidic channels.

- Sterility & maintenance: recirculation benefits with a closed loop and maintaining sterile environment.

Principles of Recirculation in Microfluidics

How to set up the microfluidic circuit for recirculation?

In a pressure-based microfluidic setup, controlled recirculation is achieved by combining valves, pressure controllers, and flow sensors in a coordinated way. A common architecture uses two 2-Switch™ valves, one Switch EZ™, two Flow EZ™ pressure controllers, and two flow sensors.

The principle is similar to alternating traffic lights on a one-way street:

while one reservoir supplies fluid to the chip, the other is refilled. The system then switches roles, allowing the same liquid to circulate continuously in a single direction through the microfluidic chip.

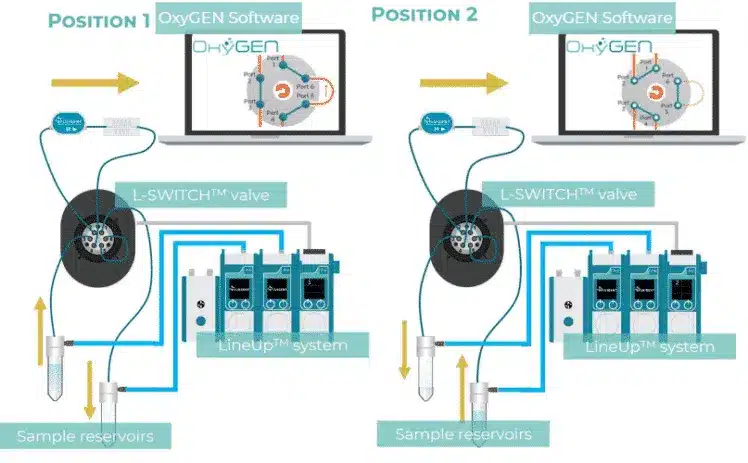

The pressurized reservoirs and valves alternate automatically, ensuring unidirectional flow while enabling closed-loop recirculation within a single chip. An alternative configuration uses an L-Switch™, which follows the same principle but with a different valve geometry. Both configurations are supported by pre-programmed functions in the OxyGEN software, allowing users (including beginners) to set up recirculation without advanced programming or fluidic expertise.

Figure 1: Recirculation package using 2-Switch™ configuration

Figure 2: Recirculation package using 2-Switch™ and L-Switch™ configuration

Peristaltic pumps: why are they often not ideal?

Some workflows achieve recirculation using peristaltic pumps, which move fluid by repeatedly compressing flexible tubing. The fluid is pushed forward, but in discrete pulses rather than as a smooth, continuous stream.

Although this approach enables circulation between the same reservoir and the microfluidic chip, it has well-documented limitations. In peristaltic pumping, flow pulsation is directly linked to the rotor speed. While the average flow rate corresponds to the commanded setpoint, the instantaneous flow can exhibit oscillations up to 40% of the target flow rate.

These flow oscillations can disrupt shear-stress-sensitive cells, potentially causing membrane stress, cell detachment, or reduced cell viability. As a result, peristaltic pumps are generally not well suited for applications that require stable, continuous laminar flow, such as vascular or endothelial models where shear stress must be tightly and reproducibly controlled.

Other technologies, such as syringe pumps, can also be used but come with important constraints, such as the finite syringe volume limits experiment duration, making them impractical for long-term studies and slow flow stabilization and poor responsiveness

Syringe pumps are typically better suited for short, single-pass experiments rather than recirculating systems.

To read in depth comparison of various flow control technologies read this blog.

Automated integrated pressure-based platforms

Custom Platforms

Endothelial cell culture under controlled shear stress is one of the most common and demanding use cases for long-term recirculation with precise flow control.

In a study published in Micromachines (2022), a pressure-driven perfusion system was implemented using a custom-designed fluidic splitter to enable accurate, multiplexed recirculation for organ-on-chip applications. The system incorporated dedicated flow-rate measurement lines, validated the flow sensors, and demonstrated stable bead perfusion for 48 hours, confirming reliable long-term operation(1).

Figure 3: Pressure-based Custom-made Fluidic Circuit Board by Graaf N.S. (2022)

Omi: Organ-on-Chip Fluidic Platform

The Omi™ platform is designed specifically for long-term recirculation and organ-on-chip experiments. It integrates:

- Pressure sources

- Valves

- Pressure and flow sensors

- Optical level sensors for system validation

The system uses a sterile, consumable cartridge that includes check valves, enabling recirculation, perfusion, and injection steps within the same setup.

Figure 4: Omi for Long term Reciculation

The Omi™ operates using Fluigent’s proprietary Smart Flow Technology, which pressurizes reservoirs to deliver reproducible, flow-rate-controlled recirculation. The OOAC system validated for over 7 days of continuous recirculation, while significantly reducing contamination risk and manual handling compared to traditional setups.

In practical terms, the system functions as a self-regulating circulation loop, continuously monitoring and adjusting flow conditions to maintain stable, physiologically relevant environments over extended periods.

4 Key Applications of Microfluidic Recirculation in Life-Sciences

1. Organ-on-Chip (OOC) Controlled Shear Stress

Recirculation plays a critical role in organ-on-chip (OOC) systems by enabling physiologically relevant dynamic environments. Beyond providing a continuous supply of nutrients and oxygen, recirculation allows researchers to apply controlled and sustained shear stress, while maintaining a stable microenvironment for cells over extended periods.

Pressure-controlled recirculation is often preferred in OOC applications because it delivers stable, low-pulsation flow, which is essential for accurately reproducing physiological shear stress. Compared with peristaltic-based recirculation, pressure-driven systems offer improved flow stability and reproducibility, which is particularly important for shear-sensitive cell types such as endothelial cells.

A representative example is the artery-on-chip (AoC) model developed by Paloschi et al. (2023)(2). In this study, endothelial cells (ECs) and smooth muscle cells (SMCs) were co-cultured under high-shear conditions to replicate arterial flow. The platform was used to investigate how changes in shear stress influence vascular structure and to evaluate the effects of the anticancer drug Lenvatinib on a multicellular arterial model.

Figure 5: Immunofluorescence staining of the AoC membrane showing ECs and SMCs labeled with their respective markers (PECAM for ECs and SM22 for SMCs). The AoC is connected to a microfluidic pressure controller (MFCS) to ensure precise flow regulation.(2)

These results demonstrate that accurately reproducing hemodynamic flow conditions on chip is essential for understanding vascular pathologies, including aneurysm formation mechanisms.

Similarly, a study published in Brain Sciences (2022) optimized and adjusted shear stress parameters in a microfluidic intracranial aneurysm model. By fine-tuning flow conditions, the authors showed how shear stress influences vascular remodeling and disease progression in brain-specific contexts(3).

Figure 6: Schematic of an organ-on-chip recirculation setup using pressure-based flow control to achieve precise, stable shear stress in microfluidic channels.(3)

2. Long-Term Culturing: Adherent Cells, Organoids and Tissue Models under Flow

For experiments lasting days to weeks, such as tissue differentiation, organoid culture, co-culture systems, recirculation conserves medium, reduces reagent costs, and maintains medium composition over time.

Beyond sustaining long-term organoid viability, controlled microfluidic perfusion also enables the integration of immune components, which play a crucial role in tissue homeostasis and disease response. Despite their importance, immune cells are still rarely incorporated into organ-on-chip (OoC) models.

Recent work has shown that culturing B and T lymphocytes within a 3D hydrogel microchip under continuous fluid flow can drive the formation of lymphoid follicles in vitro.

In this context, fluid flow was essential not only for follicle formation but also for preventing unintended immune cell autoactivation.

Figure 7: Differences observed on Lymph node on-a-chip. When Medium is perfused in upper channel(4)

3. Sample Enrichment for Analytical Assays

Recirculation enables low-volume, repeated exposure of cells or analytes to assay zones. For non-adherent or rare cells (e.g., leukocytes, circulating tumor cells, stem cells), recirculation conserves precious sample volume and allows repeated interaction with sensing or stimulation regions, improving assay efficiency.

In recent microfluidic platforms, recirculation has been used to keep cells in suspension, preventing sedimentation while repeatedly passing them through defined culture or analysis chambers. This approach has proven particularly useful for immune cell assays and tumor–immune interaction studies, where maintaining cell viability and avoiding unintended activation are critical. By combining gentle flow with closed-loop circulation, these systems enable prolonged observation, functional readouts, and repeated stimulation of the same cell population without excessive dilution or loss of rare cells.

Conclusion

Recirculation is a powerful technique in microfluidic life-science applications, especially for organ-on-chip, long-term cell culture, and sample-limited experiments. When properly implemented, pressure-controlled recirculation enables efficient use of media and reagents.

Related Instruments

Related content

-

Expert Reviews: Basics of Microfluidics Automation in Microfluidics: Real-Time Monitoring and Feedback Loops Read more

-

Expert Reviews: Basics of Microfluidics 5 Key Tips for Starting Organ-on-Chip Models Read more

-

Microfluidic Application Notes Liver–Kidney Organ-On-Chip Model using the Omi™ Dual Platform Read more

-

Microfluidics Case Studies Gut-on-Chip Modeling: From Chip Development to Perfusion Read more

-

Microfluidic Application Notes Controlling Flow Rate and Shear Stress with Omi™ to Study Endothelial Cell Response Read more

-

Microfluidic Application Notes Gut-on-Chip Model Development Using OOAC Platform, Omi Read more

-

Microfluidic Application Notes Long-term fluid recirculation system for Organ-on-a-Chip applications Read more

-

Microfluidics White Papers A review of Organ on Chip Technology – A White Paper Read more

-

Expert Reviews: Basics of Microfluidics Why Control Shear Stress in Cell Biology? Read more

-

Microfluidic Application Notes Peristaltic Pump vs Pressure-Based Microfluidic Flow Control for Organ on Chip applications Read more

References

1. Graaf MNS de, Vivas A, Meer AD van der, Mummery CL, Orlova VV, Graaf MNS de, et al. Pressure-Driven Perfusion System to Control, Multiplex and Recirculate Cell Culture Medium for Organs-on-Chips. Micromachines [Internet]. 2022 Aug 20 [cited 2025 Dec 15];13(8). Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2072-666X/13/8/1359

2. Paloschi V, Pauli J, Winski G, Wu Z, Li Z, Botti L, et al. Utilization of an Artery-on-a-Chip to Unravel Novel Regulators and Therapeutic Targets in Vascular Diseases. Adv Healthc Mater. 2024;13(6):2302907.

3. Vivas A, Mikhal J, Ong GM, Eigenbrodt A, Meer AD van der, Aquarius R, et al. Aneurysm-on-a-Chip: Setting Flow Parameters for Microfluidic Endothelial Cultures Based on Computational Fluid Dynamics Modeling of Intracranial Aneurysms. Brain Sci [Internet]. 2022 May 5 [cited 2025 Dec 15];12(5). Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3425/12/5/603

4. Juste-Lanas Y, Hervas-Raluy S, García-Aznar JM, González-Loyola A. Fluid flow to mimic organ function in 3D in vitro models. APL Bioeng. 2023 Aug 4;7(3):031501.

Author: Anel, Dec. 16 25